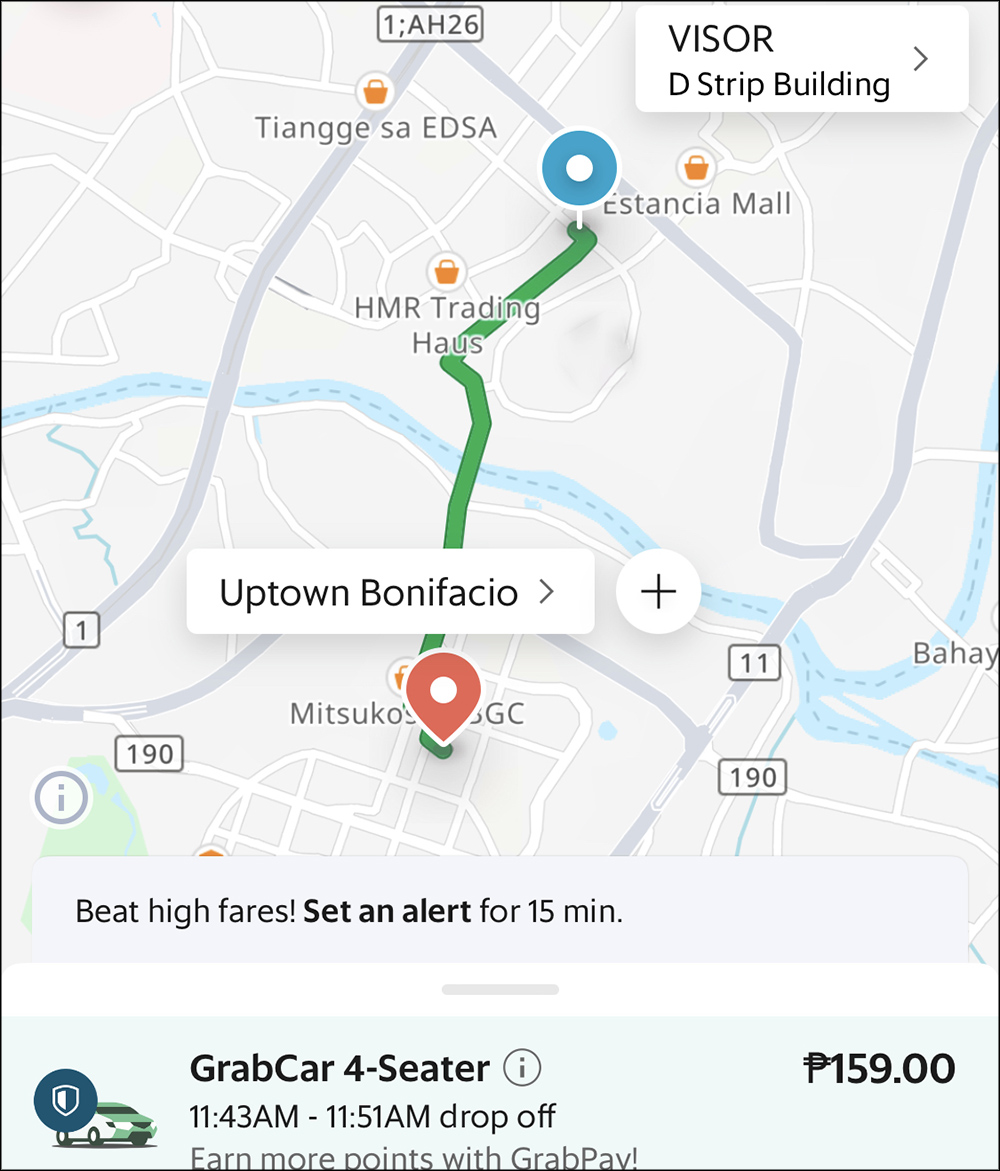

In a move that is almost certainly many years too late, the Land Transportation Franchising and Regulatory Board has formally asked Grab, the biggest Transport Network Company (TNC) still operating in the Philippines, to explain its methodology behind the so-called surge pricing—how the app calculates and implements price increases based on demand. Specifically, the LTFRB asked to see ”how Grab arrived at this fare rate and asked the company to present their computation on ‘surge’ fees.”

It’s interesting that we still use the term “surge” fees, which was the name used by Grab’s now-defunct (in the Philippines at least) competitor Uber. While the more general term would be something like “demand-responsive” pricing, the fact that “surge” has become shorthand for the mechanism shows how TNCs have become ubiquitous, important and, some would claim, even essential to life in the Philippines.

With public transport still suffering from queues and service interruptions, and cycling infrastructure still far off from an Amsterdam-like ideal, TNCs have, in the minds of many, taken up space as an essential form of transportation. People have demanded that the LTFRB regulate TNCs to keep prices low, and for the most part, the LTFRB has responded. This latest communication from the LTFRB seems to step in that direction again, by asking Grab to explain, presumably, why prices are high.

There are a few ways that the LTFRB could approach this. The LTFRB needs to make sure that the companies disclose their surge pricing and algorithms in a clear, digestible format. It certainly is a challenge to turn lines of code into a filing relayed in narrative form.

More than that, they need to eventually reveal the objective here. Are they trying to keep TNC prices low? Are they trying to ensure drivers are paid minimum wage? Or are there other objectives?

LTFRB has an opportunity to force TNCs to “open their books” here, and really show that they are, as the TNCs themselves say, not vultures profiting from a transport crisis.

Of course, a win-win solution may be more difficult than some may think. Software engineer Gergely Orosz, who used to work for Uber, has called the TNC business a “three-sided marketplace” where drivers, customers as well as the TNC companies themselves have competing incentives that interplay with market forces.

In structuring a TNC business model, he says it is usually possible to make one of the players happy and the others unhappy, difficult to make two happy, and practically impossible to make all three happy. Regulation can tip the scales one way or the other, but it is difficult to create a win-win-win solution.

For instance, in the Netherlands, Uber drivers can cancel on passengers without penalties. This rule was put in place to make Uber compliant with Dutch regulations regarding treating the drivers as contractors and not employees—they would be considered employees if Uber compelled them to take passengers.

This, obviously, is good for drivers, and allows Uber to avoid categorizing them as employees (thus not having to pay them minimum wage and benefits), but is not as beneficial for passengers. Governments need to make such trade-offs in thinking about regulating TNCs.

A better, more consistently applied rule would be for LTFRB to require all TNCs to disclose to the agency and the public how such fees are calculated and applied in the form of a regulatory filing. The LTFRB could prescribe exactly what kind of information needs to be provided by the company, although the more prescriptive they want to be, the more tech-savvy the agency should be in return.

This could also be a good opportunity to make sure that companies are not using other forms of data from the user to tailor surge pricing. It wouldn’t be out of the realm of possibility for some TNCs to charge more to women than men, for instance, if they notice more women use the app.

Of course, what forms of surge pricing are acceptable is up to the LTFRB, but at the very least they should make companies disclose information that could reveal inherent biases. Just because something is done by algorithm doesn’t mean it is automatically unbiased.

When the TNC app updates such that the surge fee algorithm or structure is changed, the TNC should be required to make a new filing to LTFRB, informing them of the change. This is a regulatory space with plenty of possibilities, but even now the LTFRB should be shoring up its technical capacity to evaluate what it is regulating.

The flip side of this whole discussion is, of course, whether or not we should be putting price caps on TNC services in the first place. While TNCs provide a form of transportation, they do not provide an essential form of transportation in the same way that we would regard public transportation or safe streets.

If TNC services feel essential, that’s only because the government has allowed the alternatives to be so poor and unsafe that they offer the best alternative in some people’s cases. It would be like asking the government to subsidize and provide access to fast food because fresh produce has become inaccessible—which, now that I’m typing that out, seems dangerously close to happening!

The fast-food analogy also works because, just like fast food, there are social effects to the promotion of car transportation, many of which are undesirable even in a situation where traffic is heavy and public transportation is limited. The more people we put in cars by way of cheap TNCs, the more congested our streets get even for those of us who are so poor that they cannot afford TNCs at all.

Is it fair to make “improvements” at their expense? Questions like these may end up being the most important of all as the LTFRB explores new ways to regulate TNCs like Grab.

0 Comments