COVID-19 cases are on the rise again. Alarm bells are ringing all over, and naysayers are out in force calling for stricter protocols. The seeming gains of the past month in terms of bringing down the case count to the hundreds is about to get thrown out the window. Shame.

Unfortunately, in my view, the rise in number of cases in the Philippines is a trailing (rather than a leading) indicator of the health of our populace. Why? Because people go for testing only when they already have symptoms—or, sadly, when they are already being admitted to healthcare facilities for treatment. By that time, it’s too late, and confinement is the only recourse. As a result, the ability of our front line to cope with the already rampant surge in cases is hugely handicapped. Reaction time is severely limited.

With the move of government toward economic recovery, mobility will need to be allowed to a much larger degree. People need to go to work, and consumers need to be ferried to commercial establishments. Otherwise, the restart of business is meaningless. But, with the rise in mobility comes the enhanced risk of spreading the virus. Allowed capacity of public utility vehicles are now at 75% from only 50% before. Social distancing in public transport, while still provided for, is less likely to be maintained. The mandatory wearing of masks is also loosely enforced (as is the disinfection of vehicles after each trip). Indeed, the increased mobility of people under reduced COVID Alert Levels enables the spread of the virus.

The key, of course, is the continued strict enforcement of minimum health protocols—mask, distancing and disinfection. I contend, however, that another critical and essential part of increased mobility is the heightened need for testing. Not the kind of testing that aims to confirm our worst fears that we have somehow gotten infected. What we need is a testing culture that promotes a proactive sense of “wanting to know.” This allows us to take the proper actions for our own well-being and, just as important, to avoid infecting others. Testing is (and should be) our first line of defense. It acts as our early warning device that guides us to act responsibly as a member of society. So that even as we become more mobile, we are doing so with a heightened sense of accountability. After all, being forewarned is being forearmed.

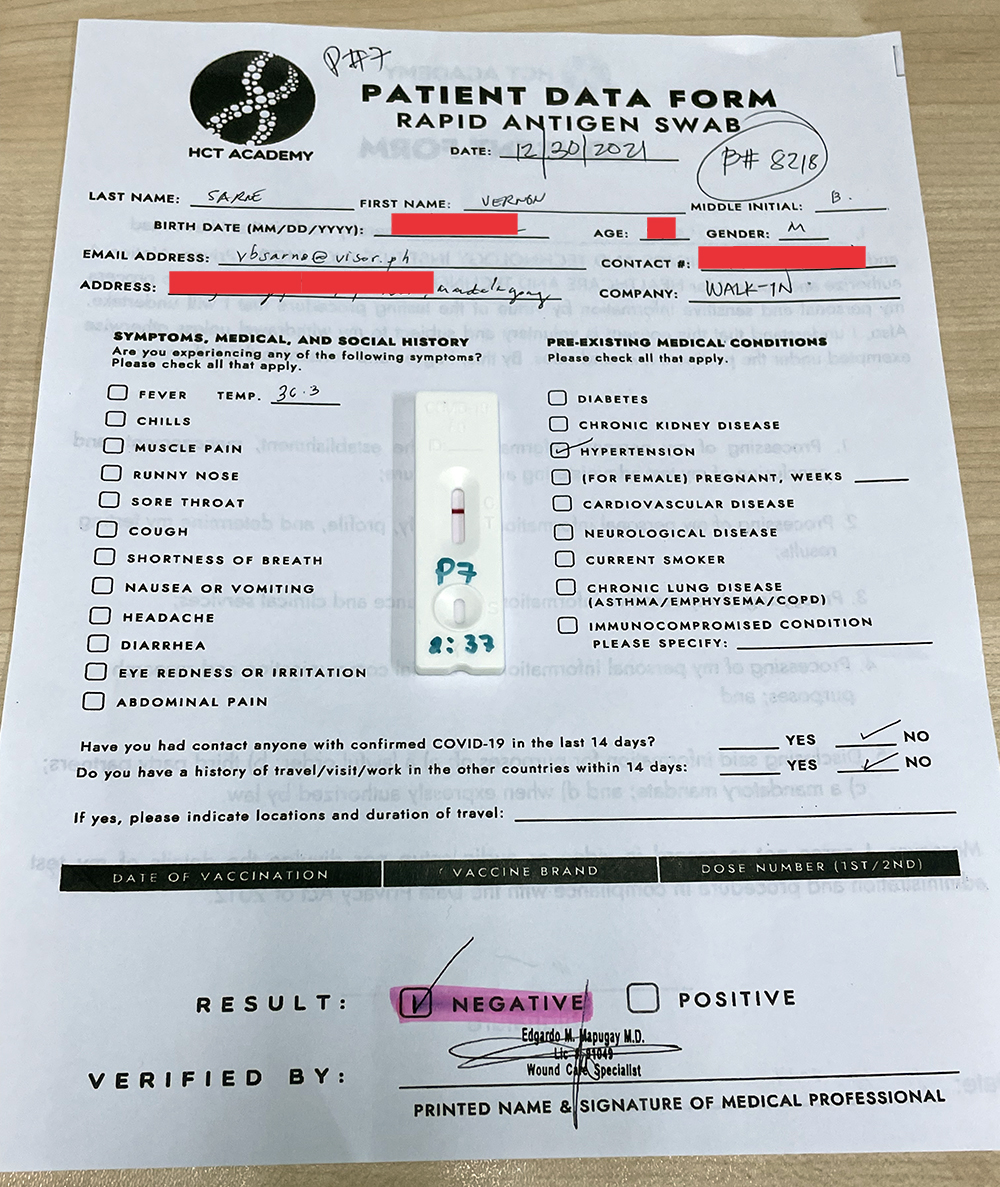

There are many reasons people do not go for testing here in the Philippines. For one, it takes a lot of money for many. Even as the scale and the scope of testing has risen, the price (not necessarily the cost) of testing has remained stubbornly high, especially the Polymerase Chain Reaction test. I recently had to take two PCR tests for traveling, and was charged P3,800 and P2,000 for pre-departure and post-arrival. If you have to spend that much money for regular testing, that will surely add up. And for the average worker, it might even amount to his entire monthly take-home pay. Of course, there is the more affordable Antigen Rapid Test, but that would still be an added cost.

Another reason is accessibility. Surely, testing has become a cottage industry with a proliferation of testing companies. The institutional ones like hospitals or Red Cross have also enhanced their capabilities. Still, unless you pay the premium for home service, you have to make the test center a destination to get yourself tested.

On these two counts, I envy the approach of some countries. I recently visited the United States and saw how robust their testing network is. It is designed with two critical factors in mind: accessibility and affordability. In New York, you can download a mobile app that tells you where you can find fixed testing centers. This is complemented by an extensive web of pop-up test stations—in stand-alone tents or mobile vans—that can be found throughout the city. Yes, they offer and do testing on the curbside. No appointments needed. Just scan the QR code, fill out the form online, and then get yourself swabbed. It takes all of five minutes, if there is no line. The results are e-mailed to you in 24-36 hours. Best of all, it is of no cost at all. Regardless of whether you are a citizen, resident or visitor, you can get yourself tested for free, on the spot, when you want to, as often as you want to.

In addition to the extensive test network, the government also provides free test kits so people can self-test in their homes. Or you can easily buy them at your nearest pharmacy.

I sense that the government encourages people to get tested, and they remove barriers for them to do so. And because New York wants to revive tourism and business, they offer the same convenience to visitors and tourists. People get tested so they can have peace of mind that they are COVID-free. This was more apparent during the holidays (which, unfortunately, were accompanied by the rapid spread of the Omicron variant). Everyone flocked to test centers because they wanted to be sure that they would not be taking the virus with them to their family gatherings or year-end celebrations.

Without testing, virus carriers would continue to be mobile and go about their lives while infecting others

This approach makes the rise in the number of cases a leading indicator that gives the healthcare sector more lead time to ramp up the critical care capacity. People are able to tell if they are infected at an early stage, and can, therefore, go into self-isolation and avoid overburdening treatment centers. While the rise in cases signals a potential rise in admissions to hospitals, asymptomatic carriers have the chance to isolate and recover on their own—thus reducing the spread. Without testing, they would continue to be mobile and go about their lives while infecting others.

There is nothing wrong in testing positive. It allows us to do the right thing, which is to care for ourselves and avoid transmitting the virus to our fellow-Filipinos.

Of course, another reason people hesitate to test is they are afraid to find out if they are, in fact, infected. This could mean that they will not be able to report for work and, thus, impair their daily or monthly earnings. Unfortunately, this is a reality that we also have to contend with. Private companies can extend sick leaves, but that is a finite benefit. Government should be able to provide ample safety nets through enhanced social welfare or “ayuda” (care) packages so people have a sense of economic assurance, no matter how small. Then, maybe, people can take responsibility for others as much as for themselves.

Testing is vital to economic recovery as much as mobility is. One without the other could be fatal.

0 Comments